Agrippa

Going back to go forward

In 1992, the designer Denis Ashbaugh and the writer William Gibson collaborated on a peculiar piece of storytelling. Part digital experiment, part Artist’s Book, part prophecy, part archeology. Agrippa is a limited edition book-as-object, presented in a case, wrapped in various linens and metals. It’s form screams ‘commemoration’ and ‘preservation’ and the title of the piece—a brand of photograph album owned by Gibson’s father, calls back to an analogue object.

The Artist’s Book isn’t a bad model to examine when making digital work. Especially as it’s inbuilt rarity appears to exist in complete contradiction to digital’s mutiplicity. Artists make books to present work and express ideas. They live within a fine print tradition, and often challenge the physical conventions of the book to the point of being unreadable.

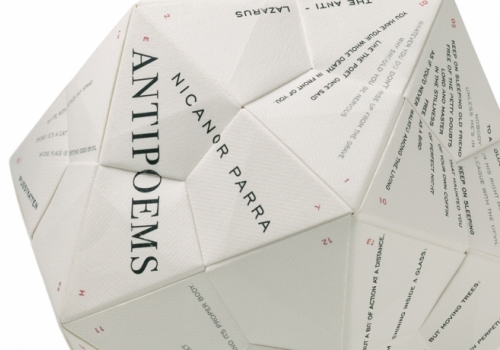

If we address their scarcity as a function of production, rather than intention (the processes used to make them are typically much more intensive than a sizable print run could accomodate), then the philosophical underpinning of the Artist’s Book as an exploration of form as it relates to content is worth serious consideration. Conveying textual elements, rather than being the primary goal of a book, are often secondary here. What is foregrounded instead is a dialogue with the book-as-object, a tactile thing to be handled and considered as well as read. Pages may open as a concertina structure, sometimes bound within a section as an interruption to the page flow. Equally likely is a three-dimensional treatment of the page sequence as something to be explored in an unlinear fashion. The whole book may be presented as one sheet of folded and cut paper, or take the form of a paper engineered object.

The nature of these approaches to making books might suggest a disregard for the reading experience, but closer examination of Artists Book practice reveals that the field is actually driven by a sincere desire to investigate the outer limits of book design, and provoke an ongoing conversation about the borders of the Avant Garde, as it might be applied to the book.

Gibson and Ashbaugh’s Aggripa is presented as follows (text reproduced from UC Santa Barbara’s exemplary Agrippa Files site, which examines the book in all its aspects and contents):

The Deluxe Edition of Agrippa comes in a heavy, distressed case. In the honeycombed bed of the under-case, wrapped in a shroud, lies the 11⅛ x 15 ⅞ x 1⅛ inch book, whose title is hand-burned into the cover. The Deluxe Edition contains 63 viewable pages with ragged, sometimes scorched edges, including copperplate aquatint etchings by Dennis Ashbaugh alluding to DNA gel patterns and body text pages consisting of dual, 42-line columns excerpting a DNA sequence from the bicoid maternal morphogen gene of the fruitfly. Page 63 (and another underlying 20 pages glued together) has a hollowed-out cavity holding the diskette with William Gibson’s poem.

Agrippa originally appeared during the earliest years of contemporary digital technology, and reflects a number of concerns under discussion during the early 1990s, many of which have not abated today. The nature of digital content as a permanent record of our lives, the nature of memory and the impact of technology on reading and the impossibility of possessing an ‘edition’ of a digital work. The entire content is reflective of a primary concern with these issues. Ashbaugh’s etchings explore our common ancestry though images printed on rag paper and presented as loose leaves inside the metal case. Gibson’s 305 line poem—a meditation on Gibson’s and his father’s youth and their relationship with the photographic images Gibson Snr made during his life—is arguably the most striking aspect of the work, and accordingly of most interest to digital writers. The poem is contained on a 1.4Mb diskette and when inserted into a 1992-era Macintosh computer, displays the whole text, line by line, as it slowly scrolls up the screen. On completion of the ‘reading’, the poem is encrypted by an additional programme within the disc, rendering it unreadable, remaining in existence only as the reader’s memory of the text, of their experience.

What makes Agrippa such a pertinent example of digital writing is the implicit connection between subject matter and overarching theme, and the manner in which technology is employed in order to foreground those themes. Genuinely, form follows content, and the two are inextricably bound together. Were the poem to remain on the disc, it would not convey the power of the central idea at its heart. Simulating the moment would not suffice either—employing javascript and css to ‘erase’ website text is fairly simple, but remove a cookie from your browser’s history and it is readable once more. For Agrippa to function as it does, the scarcity of the book form has to operate alongside the physicality of the disc—you have no backup, there is no ‘escape’ key. Reading this work renders it unreadable, and it can only persist as a shadow of itself, lodged in your memory as are Gibson’s memories of his father.

Gibson and Ashbaugh understand something vital about the connection between story, platform and their reader:

Writing for digital is not the same as writing for print. Everything is connected.